On October 3–4, parliamentary elections will be held in the Czech Republic. Some journalists, both here and abroad, are already calling them decisive not just for the Czech Republic but for the whole of Europe. At the moment I don’t know whom to vote for—or even whether to vote at all. Politicians from both sides are trying to convince me that I must.

The ruling coalition, on the brink of losing power, is putting up huge roadside billboards with the slogan: “EVERYTHING IS AT STAKE.” Its candidates on TV and social media are saying that if I don't support them this time, the opposition will sell the country to Putin. There’s some truth to that.

The opposition, in turn, claims the current government is destroying the economy and that if I let it keep power for four more years the country will be in tatters. That too seems likely.

But public choice theory, the branch of economics that studies political behavior, says I shouldn’t bother because it’s a waste of my time. It’s also mostly correct.

I.

In 1957 the American economist and political scientist Anthony Downs published the article An Economic Theory of Political Action in a Democracy, which has since become one of the most discussed and cited works in political economy. That same year Downs expanded the article into the book An Economic Theory of Democracy.

Both the article and the book explain why democracy doesn’t work, and never will work properly, and why at the helm of the state it’s often, frankly, God knows who. Downs’ argument is not the same as the popular claim that politics attracts only scoundrels and that the worst of them—those willing to trample rivals—rise to the top. That idea is easy to refute both logically and factually.

According to Downs, the unsolvable problem of democracy lies not with politicians but with voters. Not because voters are idiots, but because it simply isn’t in their interest to understand politics. Downs calls this rational ignorance. His theory can be summed up roughly like this:

To study the programs of many parties and candidates, even superficially, requires an enormous amount of time. More than that—understanding what these programs would mean for you personally requires expertise in economics, law, education, ecology, international law, and more. Not just surface-level knowledge, but real expertise—because many programs look similar and you must grasp the consequences of subtle differences. In other words, to make a truly informed choice, a voter would need the equivalent of multiple advanced degrees.

Even if some stubborn voter devotes all their free time to self-education, it won’t help much. One vote almost never makes a difference. The chance that your vote will decide an election is practically zero. You could spend months or years studying, choose the best candidate, cast your vote—only to see your effort wasted because someone else won.

And even if, by some miracle, your vote is decisive and your candidate becomes president or prime minister, you personally will gain almost nothing. Circumstances change constantly; government programs are adjusted; sudden budget shortfalls appear; coalition partners demand concessions; the opposition throws up roadblocks—so politicians usually fail to deliver even a tenth of their campaign promises. Even the promises they do fulfill change daily life for most people only marginally. At best your taxes drop a couple of percent, or your benefits rise by a few dozen dollars.

The result is that a person who invests massive time and effort into making a political choice gets zero or negligible returns. That’s why people prefer to spend their time on things that truly affect their lives: education, work, a new home or car. And they’re right—where you study and what job you take matters far more than who the next president is, at least in a democratic country. A rational person doesn’t dig through election programs but votes on intuition, “with the heart,” while devoting most of their time to more immediate concerns. That’s why, again and again, not the best candidates end up in power.

In the nearly 60 years since Downs’ article appeared, no one has provided convincing counterarguments—unless you count works like Bryan Caplan’s The Myth of the Rational Voter and Geoffrey Brennan and Loren Lomasky’s Democracy and Decision, which argue the situation is even worse.

I don’t think the tiny weight of your voice is such a huge problem. Your single voice indeed won’t change anything, but humans are surprisingly good at coordinating action even without direct communication. When enough like-minded voters make an implicit deal to vote for a particular party, single tiny votes that can’t affect anything become thousands or millions of votes that can.

The other two problems—the one of limited knowledge and the one of unreliable “representatives,” who, according to most surveys, believe they don’t have an obligation to follow the wishes of those they allegedly represent—are much bigger.

Both problems are somewhat alleviated when a country is run by referendums, like ancient Athens or, to a degree, modern Switzerland. When you vote in referendums you don’t have to be an expert in every field: you can vote on narrow topics you care about and abstain from those you don’t. The Swiss usually do exactly that: referendum turnout is often low, and that’s a good thing.

But most of us don’t live in Switzerland. Neither do I.

The Czech Republic, where I live, is perhaps the only European country with no national referendums at all. The Constitution mentions them, but there’s no law on how to hold them. In modern Czech history there’s only been one referendum—on joining the EU—and they had to pass a special law specifically for that single vote.

So instead of deciding several narrow issues twice a year like the Swiss, I have to choose once every four years the people who’ll decide those and myriad other issues for me.

Does that even make sense, considering the rational-voter problem? It does.

Representative democracy is far from perfect, but it’s preferable to any form of authoritarianism, be it open or pretending to be a democracy, like Russia or Venezuela.

Elections are an inherently blunt instrument used to handle delicate matters such as individual preferences, with results ranging from poor to terrible. But it’s an instrument nevertheless. We can’t make politicians build the world we want, but we can make them feel our ire if they’re fucking things up badly—without resorting to violence.

So yes, it makes sense to vote. And it also makes sense not to vote, depending on the situation.

Politicians on both sides always try to convince you that by staying home you give up your voice. Nonsense. You give up your voice if you always vote for the same party—the one that is “yours”—and don’t change or skip the vote even if you’re extremely unhappy. In that case you’re a silent figurine, a mere decoration.

To change politics you need to change your voice at least now and then, and sometimes withdraw it altogether.

Voting is messaging to politicians, and refusing to give your vote to anyone can be as powerful a message as giving it to somebody. It all depends on the circumstances.

Here’s mine:

II.

Twenty-six parties are competing in the upcoming election. Only seven have a chance of getting into parliament. In practice, power is contested between two: the ruling SPOLU and the opposition ANO.

SPOLU: bad on the economy

Theoretically, SPOLU should be my guys—or rather their backbone, the Civic Democrats. SPOLU is a coalition of three, and the Civic Democrats (ODS) are by far the biggest. My political positions align with ODS’s stated values.

As the Chinese, who like to count everything, would say, I have “Five Yeses” and “Three Noes.”

Five Yeses

A clear pro-Western orientation

Protection of free speech and privacy

Low taxes

Minimal bureaucracy

Referendums

Three Noes

Handouts and subsidies

Green Deal

More powers to the EU

I’m not bothered by immigration or “Islamisation,” because in the Czech Republic it isn’t really a problem. Before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine there was no mass migration here. Refugees don’t come because, unlike in neighboring Germany, they don’t get generous social benefits. The Iraqis relocated here under EU quotas, rented buses several days later and fled west. There are some 5,500 Muslims in Czechia—about 0.05% of the population.

If anything, the Czech Republic has had too few migrants: work visas for foreign labourers and specialists were issued reluctantly and slowly, leaving Czech companies chronically short of staff. Now, thanks to Ukraine’s misfortune, that problem has been partly solved.

Of the eight points above I disagree with ODS on just one: referendums. I can live with that.

It’s not just cerebral, it’s also emotional. I supported ODS for many years and had grown loyal to them. On top of that the current opposition looks unattractive—one may even say repugnant.

All in all, voting for SPOLU should be a no-brainer.

Unfortunately, it isn’t.

Though SPOLU talks low taxes, minimal bureaucracy and no handouts, the government has done the opposite.

On the eve of the parliamentary elections in October 2021 and again before the presidential elections in January 2023, SPOLU repeatedly promised not to raise taxes even by 1%. But as soon as their candidate became president they launched the biggest tax hike in more than ten years—raising income tax, property tax, social contributions, excise duties, VAT, … People now pay hundreds of euros more than before 2021.

And it’s not over: another tax increase is planned for January 2026 and will hit small entrepreneurs and the self-employed—the very electoral base of SPOLU.

Today they say that when they promised not to raise taxes they didn't know the war was coming. That’s a lie: they kept promising it eleven months after the war started.

At the same time SPOLU has been generous with subsidies. True, they inherited many from the previous government, but in four years in power they’ve done nothing about it. If anything, the situation worsened: people with above-average salaries receive financial support to rent expensive apartments in central Prague.

SPOLU promised to cut the number of public servants that ballooned under the previous government. Today it boasts of cutting 11,000 jobs in 2024. Impressive—except that in 2022 and 2023 they hired 17,000 new public servants, so there are more of them now than when SPOLU came to power.

I’m paying for it with higher taxes and, if they remain in power, will pay even more next year.

Why are they doing this?

The government says that they increase taxes to decrease the government debt, but the government debt keeps growing.

Most likely they just aren’t bold enough to cut government jobs and social spending, so they raise taxes to keep the deficit at least partly under control—at the expense of growth and prosperity. Their message to voters seems to be: we’re good enough as we are.

I wouldn’t mind so much if, instead of sponsoring rent for people richer than me, my taxes bought weapons for Ukrainian soldiers. After all, SPOLU emphasizes its support for Ukraine.

Unfortunately, here too SPOLU talks the talk but doesn’t walk the walk.

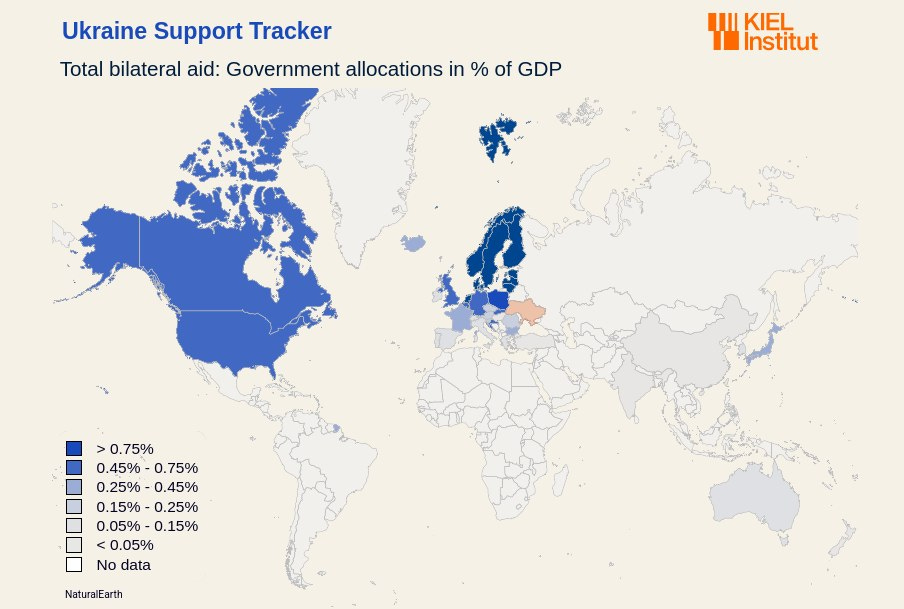

In the first year of the war Czech help for Ukraine was substantial—Czechia ranked among the top five by aid as a share of GDP. But assistance dried up in subsequent years. According to the Kiel Institute’s Ukraine Support Tracker, today Czechia is 24th by share of aid to GDP and 22nd if we count only military aid. Cumulative Czech military aid to Ukraine is 0.137% of 2021 GDP, on par with Portugal (0.136%). Slovakia, although its support ceased in 2023, was five times higher (0.686%). The leader, Denmark, gave 2.621%.

With all the pro-Ukrainian posturing, the last Czech aid transfer to Ukraine was in June 2024.

Today the main Czech contribution is the Ammunition Initiative—a pan-European program supplying Ukraine with artillery ammunition coordinated by Czechia. But it wasn’t a government invention: the program was conceived and kick-started by President Petr Pavel and his former army colleagues. The government keeps it going, which is good, but it’s hardly enough.

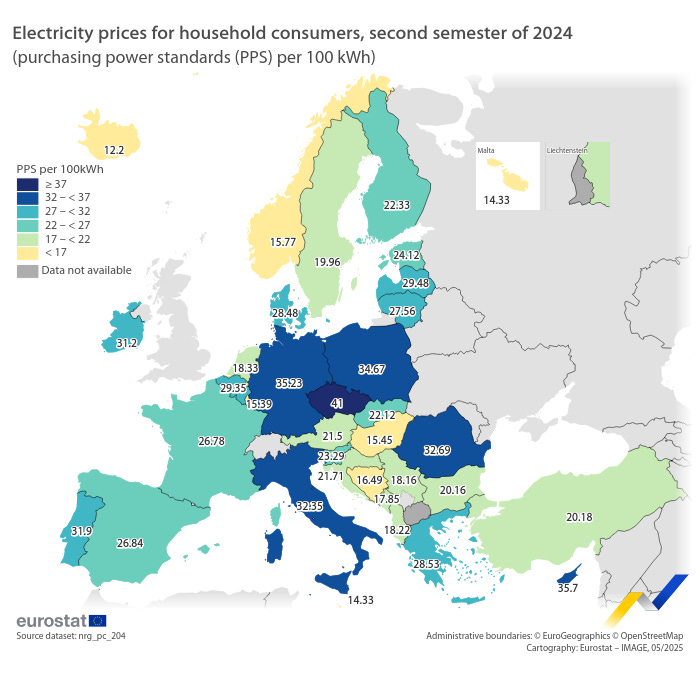

Meanwhile, the economy is stalling. Czech GDP is growing slower than in most former communist countries. Prices are soaring. Electricity is the most expensive in the EU by PPS.

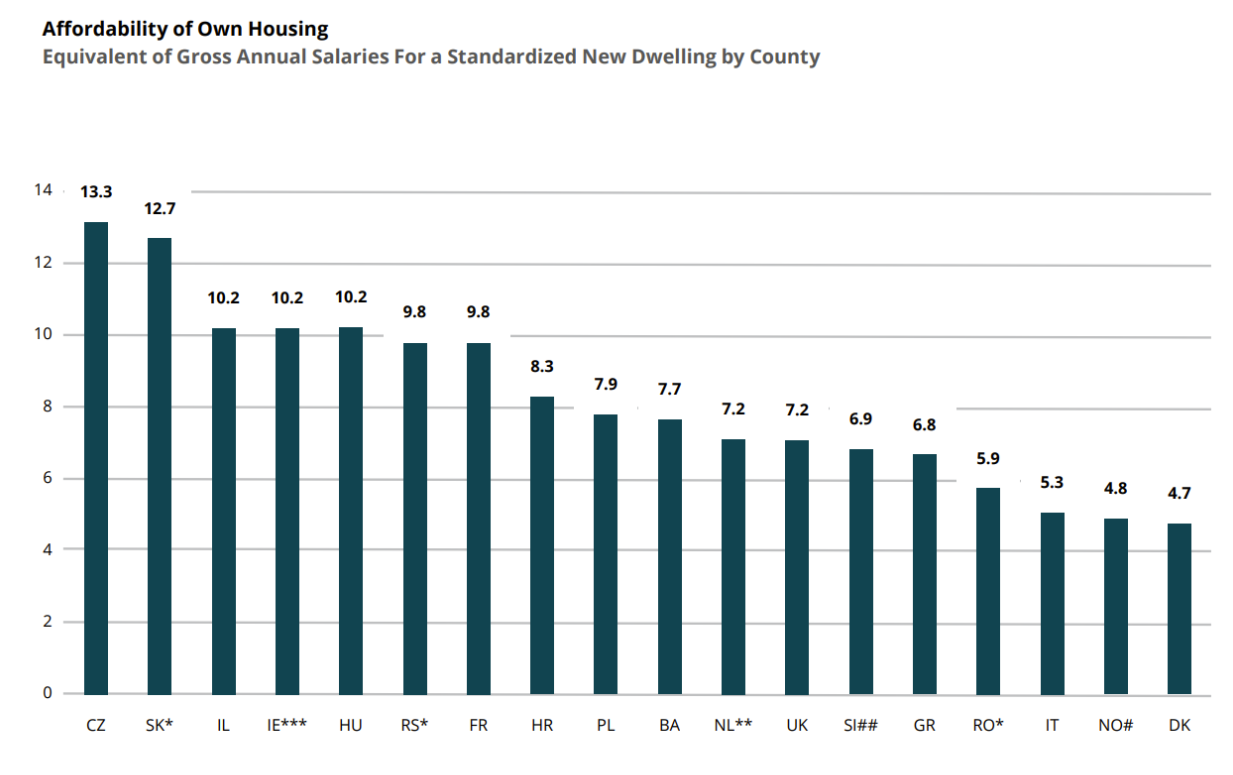

Property prices are skyrocketing—according to the last year Deloitte Property Index, Czechs must work the highest number of years in the EU to buy a home.

Another and more recent rankings from a major Czech bank gives Czechia a better position (5th from the bottom) but a worse number: 13.6 years instead of 13.3.

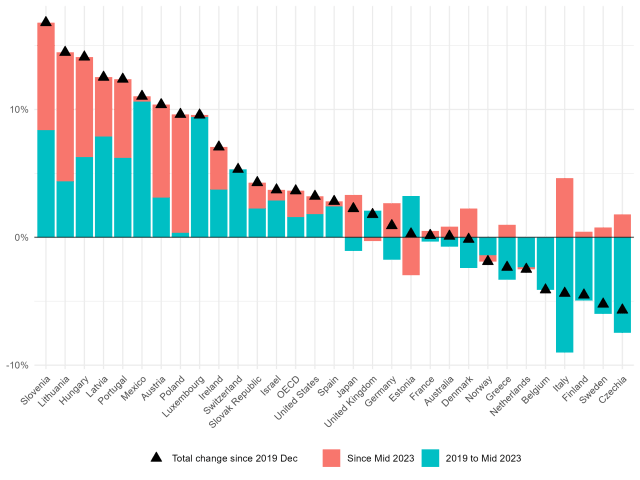

Real wages are still lower than in 2019—in fact, OECD data shows that by wage recovery since 2019 Czechia is the worst among developed economies.

Reforms are urgently needed, but there’s no plan.

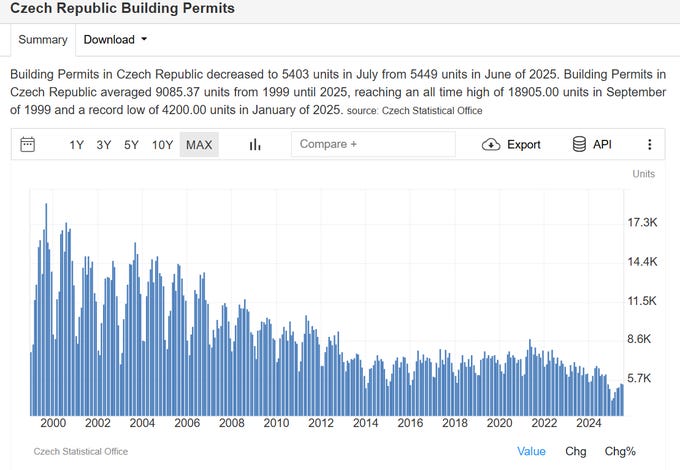

The biggest problem is the construction law—one of the worst in the world, 157th in international business rankings. Getting final permission to build anything, from an apartment block to a highway, takes many years, often more than a decade. It stalls the economy and raises costs. Foreign supermarket chains don’t want to expand to Czechia because they can’t build. High-tech companies avoid opening branches because housing is expensive. Logistic giants hesitate to create hubs because of the poor road network. Even the high price of electricity partly depends on this: Czech energy is effectively drained to more expensive, energy-poor Germany with its suicidal green policies. Czech and foreign energy companies could profit by opening new power stations and that would suppress prices—but they can’t build.

The previous government changed the law—not enough, but for the better. SPOLU changed it back soon after taking power, most likely because the party leadership includes many prominent local politicians, and the new law took the power to block new construction away from them.

The new government promised another, much better construction law, but never introduced it.

Instead, on TV, social media and billboards, SPOLU politicians keep telling us everything is good and we’re doing great.

By now you can probably guess I’m angry. Not only me: according to multiple polls, the current Czech government has the lowest approval rating in the EU.

Even if I wanted to keep SPOLU in power, it would be useless: they are set to lose. My tiny voice and the voices of other former SPOLU loyalists won’t change that. Most people have had enough.

What I and people like me could do is send SPOLU a signal—to say that blatant violation of campaign promises and four years of doing nothing is a no-go.

To make this message resonate I want their defeat to be sound and painful—painful enough to cause leadership replacement and to imprint the importance of keeping promises. Or even to cause the party’s demise and clear space for a new, more consistent right-liberal entity.

So what can I do?

III.

There are five major options.

1. Flip

The first option is to vote for the current opposition. It’s the obvious choice if you believe the opposition is better aligned with your values.

This time it’s not the case: no major opposition party passes my First Value test—all are, at best, ambiguous about supporting Ukraine, and some are openly pro-Russian.

ANO: bad on Ukraine

There are currently four opposition parties with a good chance of getting seats. The biggest is ANO, the pocket party of billionaire Babiš. It is SPOLU’s main rival and polls predict it will win but fall short of a majority.

ANO has a decent economic program—far from perfect, but probably one of the better ones in this election. Certainly better than SPOLU’s, which lacks a real program, probably because after 2021 few people would believe their promises anyway.

ANO tried to improve the construction law when in power in 2017–2021 and promise to finish that work if elected. They support referendums and reject the Green Deal. They are not terrible on privacy and free speech.

What spoils it all is their position on Ukraine—or the lack of one.

SPOLU claims ANO will sell Czechia to Russia. That looks like an overstatement. ANO leaders have repeatedly condemned Russian aggression. In 2021, when in power, they reduced the hugely inflated personnel at the Russian embassy —sending 90% of it packing—something SPOLU parties had talked about for 20 years but never did.

But ANO calls for a “diplomatic solution” to the war, which in practice would mean Ukrainian capitulation. They say they will end the Ammunition Initiative in its current form. They don’t promise to cancel it outright, only to pass responsibility to NATO, but there’s no sign NATO is eager to take it on.

Also, ANO left the liberal ALDE group and joined the new European Parliament faction created by Orbán, which is openly anti-Ukrainian.

That disqualifies ANO from my vote.

SPD and Stačilo: Putin’s buddies

There’s also SPD and Stačilo! (Enough!)—two parties that pretend to be on opposite parts of the spectrum but are in practice almost identical. The former is allegedly far-right and nationalist; the latter presents as far-left and communist. Both are effectively national-socialist—conservative on social issues and leftist economically. SPD is slightly more to the right, but only a political connoisseur would see a difference. Both are openly pro-Russian and anti-Ukrainian, so there’s no reason to vote for them.

Motoristé sobě: fishy dark horse

Finally, there’s Motoristé sobě (Motorists for Themselves). The single-issue local party created to oppose anti-car policies in Prague unexpectedly took third place in the 2024 European Parliament elections, which boosted its ambitions. They present themselves as the traditional right and have the best economic program among parties likely to pass the 5% threshold. But they are untested in big politics and nobody knows what they will do—SPOLU looked good on paper in 2021 too, and look how that turned out.

I might vote for Motorists in different times, but their position on Ukraine is ambiguous: their chairman condemns Russian aggression and agrees Czechia should help Ukraine, but insists it should do so “pragmatically,” without harming Czech security—whatever that means. It’s even worse with their electoral leader, Dolph Lundgren look-alike racing driver Filip Turek, who has claimed that NATO provoked Putin and repeatedly voted in the European Parliament against Russian sanctions and Ukrainian aid. Unlike some of his party colleagues, he’s also willing to govern with SPD and Stačilo—two parties unacceptable to me both politically and economically.

So, another no.

2. Shift

If I feel betrayed by the leading government party and want to punish it, but can’t support the opposition, I might shift to a smaller coalition party with closer positions.

Two such parties exist, though one left the coalition a year ago.

STAN: enemies of privacy and free speech

STAN is a junior coalition partner—centrist, supporting Ukraine and ambivalent about Israel. I could tolerate that and their lukewarm economic positions, but they fail my second-biggest priority: privacy and free speech.

The party backed a European proposal to break cryptography in messengers and repeatedly tried to introduce anti-privacy measures in Czechia—fortunately without success. They were more successful on free speech: they pushed through a law making “unauthorized activity for a foreign power” a criminal offence. It’s actually worse than Russia’s approach, where “activity for a foreign power“ earns you the status of a “foreign agent”, but the criminal offence hinges on failure to comply with draconian requirements. For now the law sleeps, but if someone wakes it, it could turn ugly.

Therefore, STAN is a definite no.

The Pirates: Greens by another name

The Czech Pirate Party used to be in government but left after a row with SPOLU. They are arguably the best party on privacy and they support Ukraine—they also back referendums.

Unfortunately, they are anti-Israel, poor on free speech, support the Green Deal and European federalization, and want to tax the rich, introduce anti-business regulations and subsidize everything that moves (except cars).

I disagree with them on five of my eight points.

One more no.

I’m out of easy options. The three left are clearly suboptimal. But I must choose one.

3. Dive

Theoretically, I could still vote for SPOLU, but with a twist. I want them to keep power while returning to classical-liberal roots. For that they need new leadership. They may replace leaders if they lose, but there’s a narrow path to leadership change without electoral defeat.

Czech electoral law lets you vote not only for a party but also for individual candidates on its list. You can mark up to four—it’s called preferential votes. If a candidate gets many, they move up the list and increase their chances to be elected. There have been cases when candidates from deep on the list shot up and replaced prominent politicians on the top.

But those were isolated cases. Replacing an entire leadership of a dozen people is different—and replacing them with untested candidates who may be no better or worse is kinda risky.

In any case, you can’t pull this off without a coordinated campaign. A prominent blogger, YouTuber or group must create a list of candidates to mark and advertise it for weeks. Nobody’s doing that now, and the clock is ticking.

4. Abstain

I can stay home; that would also be a signal. We have statistics showing how many people voted for each party in past elections. If a party sees its support drop dramatically—which will likely happen to SPOLU—they might conclude they’ve been doing something wrong and change.

Or they may not.

Besides raw votes there’s vote share. If many former SPOLU supporters stay home, turnout will drop and SPOLU’s share will be higher than in the situation where those voters cast ballots for someone else.

I want the message to be clear: SPOLU must lose both share and numbers.

5. Invest

The last option is to vote for a party unlikely to pass the 5% threshold now but that aligns well with my preferences and could grow later.

Luckily, there’s one.

Voluntia: a new hope (sort of)

Voluntia is a brand-new libertarian party unequivocally supporting Ukraine. According to election calculators I match them on almost 90% of topics—versus 60–65% for Motorists and SPOLU, whom I don’t trust.

Currently they’re niche, with strong followings in libertarian and crypto circles, but if they approach 1% they can grow. As Milei showed, libertarians can make surprising gains.

If they get over 1.5% they’ll receive public financing. I’m not a fan of public financing for parties, but if the state is paying parties anyway, I’d prefer my kindred spirits to get a share.

Another benefit: two parties hover near the 5% threshold, and the more people vote (not for them), the less likely those parties will pass it. Those are Motorists—whom I don’t care for—and the xenophobic communists from Stačilo!, whom I most want out of parliament. If a vote for Voluntia accomplish just that, it will be enough for me.

I don't know a lot about Czechia and your graphs were somewhat a revelation.

In Israel, where I happen to live you're ought to vote because there is some population that votes always, and only take the funds every time they succeed to get into a coalition.

Once my rule of thumb was to pick any non-religious right-wing part with an active civil program.

Aren't LLMs partly solving the initial problem?

You don't need to be an expert in economics and politics anymore and you don't need to read all political programs in details. You can craft some prompts and get decent recommendations from LLMs in an hour or two.

I would bet we'll see more and more people tweeting things like "ChatGPT recommended me to vote for this party and I voted" and eventually it'll become viral.